Dangers and implications of Hacktivism during the Russia-Ukraine Conflict

Published on 07 Apr 2022 | Updated on 07 Apr 2022

CyberSense is a monthly bulletin by CSA that spotlights salient cybersecurity topics, trends and technologies, based on curated articles and commentaries. CSA provides periodic updates to these bulletins when there are new developments.

OVERVIEW

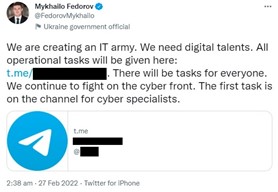

Two days after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Ukraine’s Vice Prime Minister and Minister for Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, announced the creation of the government-sanctioned “IT Army of Ukraine” – a volunteer cyber army – and requested for volunteers in Ukraine’s hacker underground to provide cyber defence for Ukraine’s critical infrastructure, as well as carry out offensive cyber operations against Russia-linked entities.

Figure 1. Call for volunteers for the "IT Army of Ukraine". Source: Twitter

The “IT Army of Ukraine” is unprecedented in modern history. It quickly led to a call to arms by various groups, including the Anonymous collective and self-declared hacktivist group AgainstTheWest – previously known for leaking data obtained from the Chinese Communist Party – and also hundreds of thousands of other netizens to take up digital arms in support of Ukraine. As the global cybersecurity landscape grows increasingly fraught in the ongoing conflict, this edition of CyberSense explores how netizens have taken part in the Russia-Ukraine conflict through cyberspace, as well as the strategic, cybersecurity and ethical implications of their participation.

FRUSTRATION AND OUTRAGE FUEL HACKTIVISM

Organisationally, the “IT Army of Ukraine” effectively exists only as a channel on the Telegram messaging app, attracting anonymous hackers globally, and coordinates and crowdsources cyber-attacks on Russian assets in cyberspace. The channel’s administrators share daily updates on targets in Russia and Belarus for its more than 300,000 subscribers (at the time of writing this article) to launch Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks and take the targeted websites down.

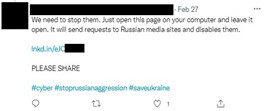

Figure 2. A post on social media sharing a malicious link that conducts DDoS attacks against Russia-related websites, and encouraging users to open the link. Source: Twitter

Many subscribers in the channel also share hacking tools on social media – some have been observed persuading friends and other users to “simply click on the link and leave your browser open to disable Russian websites” – or install software such as Disbalancer’s Liberator to “attack [Russia’s] propaganda resources”. These tools claim to carry out DDoS attacks against Russia-related websites by overwhelming the latter’s servers with floods of Internet traffic and ultimately making then inaccessible. Social media posts from subscribers often proclaim the “…need to #StopRussia” and “We have to do the right thing”, while others provide near real-time indicators of Russian websites being brought down, hoping to entice observers into taking part in the hacktivist activities. The thrill of seeing near instantaneous results of their “contributions” to the DDoS attacks may also encourage other netizens to “do more to end the war as soon as possible”.

Figure 3. Near real-time updates of Russia-related websites under DDoS attacks are also found on social media. Source: Twitter

BUT IMPLICATIONS AND DANGERS LURK AROUND THE CORNERS OF HACKTIVISM

While such users may assume they are simply pressing a button – for instance, to participate in DDoS attacks against Russian websites – there are cybersecurity and ethical implications of such involvement in the conflict.

First, any serious cyber incident resulting from hacktivism may inadvertently escalate the conflict itself, or even be used as a pretext for escalation by one side or the other. For example, pro-Russian hacker groups, including the infamous ransomware group Conti, have openly proclaimed that they would retaliate if the West attempted to target critical infrastructure in Russia or “any Russian-speaking region of the world.” Hence, these Russia-aligned hackers may potentially view participating hacktivists not as individuals, but as anti-Russian proxies from their respective countries which are not directly involved in the conflict. This consequently runs the risks of widespread reprisals and broadening the conflict in cyberspace. Cybercriminal gangs may also take advantage of such escalation to carry out opportunistic attacks, under the pretext of striking back against Russia’s enemies.

Second, cybersecurity researchers have pointed out that hacktivists often lack both the coordination and discipline to prevent collateral damage or unintended effects to uninvolved parties. The nature of hacktivism is necessarily ‘loud’ – since the objective is often to make a statement of intent – but uninvolved parties have been observed to be embroiled or impacted by their activities. For instance, a German firm, Rosneft Deutschland, suffered a cyber-attack allegedly carried out by hackers claiming to represent the Anonymous collective, which wanted to get at Rosneft – a major Russia state-owned petroleum company.

Third, some of the hacking tools that are widely shared by hacktivists have been observed to incorporate malware. Cybersecurity researchers have warned that such hacking tools are not secure, and do not protect user privacy and anonymity. They collect personal data such as usernames, IP addresses, as well as physical location derived from these user IP addresses, putting users at risk of reprisal. More worryingly, researchers have also highlighted how some of these tools, while claiming to carry out DDoS attacks against Russian targets, could in fact be targeting other victims instead, based on the tool operators’ intentions. Separately, malware have been observed masquerading as hacking tools, such as Disbalancer and Liberator, which have been shared openly in various social media platforms to crowdsource cyber-attacks. Instead of launching DDoS attacks, these spoof versions steal cryptocurrency-related information and login credentials from devices where they have been installed, then upload them to the malicious actor’s Command and Control (C&C) server.

REGARDLESS OF MOTIVATION, HACKING IS A CRIMINAL OFFENCE IN SINGAPORE

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, hacking is illegal in many jurisdictions, including Singapore. Regardless of motivation or reason, participating in any hacktivist activity, such as defacing websites and carrying out DDoS attacks, is a criminal offence in Singapore under Singapore’s Computer Misuse Act (CMA), something anyone considering partaking in cyber activities against either combatant should bear in mind. The resurgence of global hacktivism, which has been receding for several years, is a timely reminder for organisations to manage relevant risks related to the cyber-attacks being carried out in tandem with the Russia-Ukraine conflict, including collateral damage arising from hacktivist activity. As the conflict enters its fifth week, organisations should also remain vigilant, and take all necessary actions to review their security preparedness and strengthen their cybersecurity posture.

SOURCES INCLUDE:

ABC News, Avast, Bloomberg, Cisco Talos, CyberNews, Facebook, Financial Times, Politico, SC Magazine, Singapore Statutes Online, TechRepublic, The Conversation, The Guardian, The Independent, The Times of Israel, The Verge, The Washington Post, Threatpost, Tiktok, TODAY Singapore, Twitter, Wired.